Linux Kernel Meltdown Mitigation Analysis

Meltdown is a hardware security vulnerability that primarily affects various processors, including those from Intel, AMD, and ARM. Modern processors use a mechanism called “speculative execution”, where they predict and execute instructions that might be needed in advance. Programs may execute instructions that would never be reached, but these instructions can cause memory access and affect the data cache. Meltdown untilizes this feature by using differences in data access speeds to side-channel data inaccessible to a normal user.

Since CPU bugs are hard to fixed, OS mitigates them through software level. For example, Linux uses a mechanism called Kernel Page Table Isolation (KPTI) to reduce the impact of the attack.

1. KPTI

The Linux kernel implements the KPTI to mitigate Meltdown. It separates the page tables used by user space and kernel space. When a process runs in user space, it uses the user space page table. Only if entering kernel space by syscall or exception, it switches to the kernel page table. This separation prevents processes from using side channels to access kernel space data. For more details, you can refer to the official documentation.

To enable KPTI, you need to add CONFIG_PAGE_TABLE_ISOLATION=y in the kernel configuration file. This config will implement the following assembly macro:

# arch/x86/entry/calling.h

.macro SWITCH_TO_KERNEL_CR3 [...]

.macro SWITCH_TO_USER_CR3_NOSTACK [...]

.macro SWITCH_TO_USER_CR3_STACK [...]

.macro SAVE_AND_SWITCH_TO_KERNEL_CR3 [...]

.macro RESTORE_CR3 [...]

These macros are used during the switch between user space and kernel space. For example, the syscall entry point entry_SYSCALL_64 uses the macro SWITCH_TO_KERNEL_CR3 at the beginning to switch to the kernel page table [1].

SYM_CODE_START(entry_SYSCALL_64)

[...]

swapgs

movq %rsp, PER_CPU_VAR(cpu_tss_rw + TSS_sp2)

SWITCH_TO_KERNEL_CR3 scratch_reg=%rsp # [1]

[...]

Interestingly, if we loop back to see the definition of SWITCH_TO_KERNEL_CR3, we will find that this macro doesn’t just update cr3. Instead, it is wrapped through another macro called ALTERNATIVE [2].

.macro SWITCH_TO_KERNEL_CR3 scratch_reg:req

ALTERNATIVE "jmp .Lend_\@", "", X86_FEATURE_PTI # [2]

mov %cr3, \scratch_reg

# [...]

.Lend_\@:

.endm

The ALTERNATIVE asm macro takes three parameters: the old instruction, the new instruction, and flags. These assembly codes are defined in the .altinstructions section. Each ALTERNATIVE macro represents a struct alt_instr object.

#define ALTERNATIVE(oldinstr, newinstr, ft_flags) \

OLDINSTR(oldinstr, 1) \

".pushsection .altinstructions,\"a\"\n" \

ALTINSTR_ENTRY(ft_flags, 1) \

".popsection\n" \

".pushsection .altinstr_replacement, \"ax\"\n" \

ALTINSTR_REPLACEMENT(newinstr, 1) \

".popsection\n"

During the compilation stage, linking is performed based on vmlinux.lds.S, and the .altinstructions section is encapsulated between two variables: __alt_instructions and __alt_instructions_end.

.altinstructions : AT(ADDR(.altinstructions) - LOAD_OFFSET) {

__alt_instructions = .;

*(.altinstructions)

__alt_instructions_end = .;

}

Alternation is a mechanism in the Linux kernel designed to optimize for different CPU types, with implementations varying based on the instruction set. The x86 kernel patches the kernel code during the initial function alternative_instructions(). Besides optimizing certain instructions, it also iterates through all struct alt_instrobjects registered via the ALTERNATIVE macro at compile time [3].

void __init alternative_instructions(void)

{

// [...]

apply_alternatives(__alt_instructions, __alt_instructions_end); // [3]

// [...]

}

The function alternative_instructions() first checks if the CPUID has enabled the corresponding capability, such as X86_FEATURE_PTI [4]. It then calls text_poke_early() [5] to replace the old instruction.

void __init_or_module noinline apply_alternatives(struct alt_instr *start,

struct alt_instr *end)

{

struct alt_instr *a;

// [...]

for (a = start; a < end; a++) {

instr = (u8 *)&a->instr_offset + a->instr_offset;

// [...]

if (!boot_cpu_has(a->cpuid) == !(a->flags & ALT_FLAG_NOT)) { // [4]

optimize_nops_inplace(instr, a->instrlen);

continue;

}

// [...]

insn_buff_sz = a->replacementlen;

for (; insn_buff_sz < a->instrlen; insn_buff_sz++)

insn_buff[insn_buff_sz] = 0x90;

// [...]

text_poke_early(instr, insn_buff, insn_buff_sz); // [5]

}

}

The enabling of X86_FEATURE_PTI is related to the kernel boot parameters and is handled by the init function pti_check_boottime_disable(). This function initially sets the PTI mode to AUTO. If it detects that the kernel does not support CPU mitigation during booting [6], or if the boot parameters "pti=off" [7] or "nopti" [8] are provided, PTI is forcibly disabled. Conversely, if "pti=on" is specified, PTI is enabled [9], and the CPU capability X86_FEATURE_PTI is activated. In AUTO mode, the function checks if the current CPU is affected by the Meltdown bug (X86_BUG_CPU_MELTDOWN) [10]. If the CPU is not affected, PTI remains disabled; otherwise, PTI is enabled.

void __init pti_check_boottime_disable(void)

{

char arg[5];

int ret;

// [...]

pti_mode = PTI_AUTO;

// [...]

ret = cmdline_find_option(boot_command_line, "pti", arg, sizeof(arg));

if (ret > 0) {

if (ret == 3 && !strncmp(arg, "off", 3)) {

pti_mode = PTI_FORCE_OFF; // [7]

pti_print_if_insecure("disabled on command line.");

return;

}

if (ret == 2 && !strncmp(arg, "on", 2)) {

pti_mode = PTI_FORCE_ON; // [9]

pti_print_if_secure("force enabled on command line.");

goto enable;

}

// [...]

}

if (cmdline_find_option_bool(boot_command_line, "nopti") || // [8]

cpu_mitigations_off()) { // [6]

pti_mode = PTI_FORCE_OFF;

pti_print_if_insecure("disabled on command line.");

return;

}

autosel:

if (!boot_cpu_has_bug(X86_BUG_CPU_MELTDOWN)) // [10]

return;

enable:

setup_force_cpu_cap(X86_FEATURE_PTI);

}

To observe the effect of ALTERNATIVE, let’s continue with the example of entry_SYSCALL_64. When PTI is enabled, the assembly code of entry_SYSCALL_64 updates the cr3 register, which stores the page table [11].

<entry_SYSCALL_64>: swapgs

<entry_SYSCALL_64+3>: mov QWORD PTR gs:0x6014,rsp

<entry_SYSCALL_64+12>: xchg ax,ax

# [11]

<entry_SYSCALL_64+14>: mov rsp,cr3

<entry_SYSCALL_64+17>: nop DWORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

<entry_SYSCALL_64+22>: and rsp,0xffffffffffffe7ff

<entry_SYSCALL_64+29>: mov cr3,rsp

<entry_SYSCALL_64+32>: mov rsp,QWORD PTR gs:0x32398

# [...]

Conversely, if PTI is not enabled, the original assembly code is used, which includes a jmp instruction. This version directly executes a jmp to skip over the instructions that would update the cr3.

<entry_SYSCALL_64>: swapgs

<entry_SYSCALL_64+3>: mov QWORD PTR gs:0x6014,rsp

<entry_SYSCALL_64+12>: jmp 0xffffffff826000a0 <entry_SYSCALL_64+32> ---- # [12]

# [...] |

<entry_SYSCALL_64+32>: mov rsp,QWORD PTR gs:0x32398 <-----------------

# [...]

2. cpu_entry_area

2.1 Overview

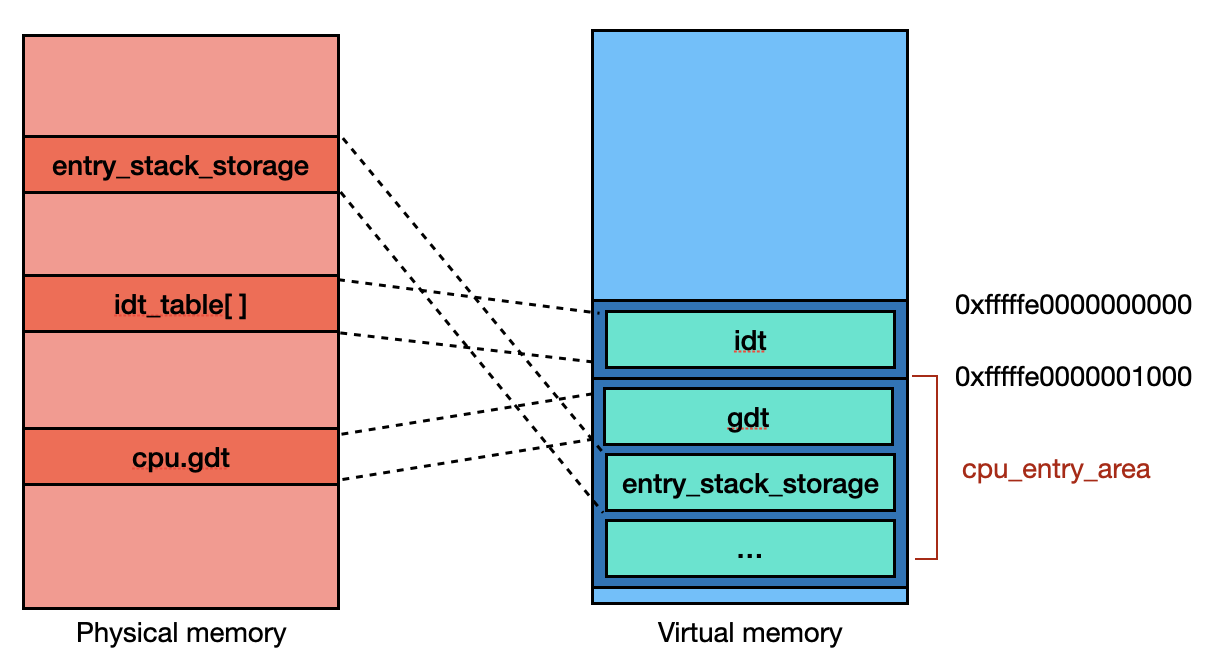

However, the user space page table still needs to know and access a small portion of the kernel data, such as the address of IDT, which is used to define interrupt handlers, so that the system can know which kernel function should be called when the exception occurs. This information is stored in a compile-time-fixed memory region known as the cpu_entry_area. A reply in an article on StackExchange provides a simple overview of the cpu_entry_area. You can refer to the post here.

Referencing the Linux kernel x64 memory layout documentation, it can be noted that the cpu_entry_area memory region starts at 0xfffffe0000000000 [1]. This region is mapped at a fixed location regardless of whether KASLR (Kernel Address Space Layout Randomization) is enabled or not.

# [...]

fffffc0000000000 | -4 TB | fffffdffffffffff | 2 TB | ... unused hole

| | | | vaddr_end for KASLR

fffffe0000000000 | -2 TB | fffffe7fffffffff | 0.5 TB | cpu_entry_area mapping # [1]

# [...]

2.2 Initialization

The memory mapping of cpu_entry_area is accomplished by the initialization function setup_cpu_entry_area(). This function remaps various components, including but not limited to the GDT (Global Descriptor Table) [2] and the exception stack [3], to the cpu_entry_area. It is important to note that the address of the struct cpu_entry_area object is located in 0xfffffe0000001000, not 0xfffffe0000000000. The first 0x1000 bytes are reserved for the IDT, which will be initialized later.

static void __init setup_cpu_entry_area(unsigned int cpu)

{

struct cpu_entry_area *cea = get_cpu_entry_area(cpu);

// [...]

cea_set_pte(&cea->gdt, get_cpu_gdt_paddr(cpu), gdt_prot); // [2]

cea_map_percpu_pages(&cea->entry_stack_page, // [3]

per_cpu_ptr(&entry_stack_storage, cpu), 1,

PAGE_KERNEL);

// [...]

}

Next, when initializing the interrupt request (IRQ), the function init_IRQ() is called. This function, at a lower level, calls idt_map_in_cea() to map the idt_table[] to CPU_ENTRY_AREA_RO_IDT_VADDR, which is 0xfffffe0000000000 [4].

static void __init idt_map_in_cea(void)

{

cea_set_pte(CPU_ENTRY_AREA_RO_IDT_VADDR, __pa_symbol(idt_table), // [4]

PAGE_KERNEL_RO);

idt_descr.address = CPU_ENTRY_AREA_RO_IDT;

}

Subsequently, the kernel continues its initialization process, and the IDT is updated several times. For instance, the page fault handler IDT early_pf_idts[] is copyed to idt_table[] when kernel is setting up early page fault.

static const __initconst struct idt_data early_pf_idts[] = {

INTG(X86_TRAP_PF, asm_exc_page_fault),

};

void __init idt_setup_early_pf(void)

{

idt_setup_from_table(idt_table, early_pf_idts,

ARRAY_SIZE(early_pf_idts), true);

}

Additionally, before the kernel is fully operational, start_kernel() calls trap_init() to update the trap interrupt vector. The underlying function idt_setup_traps() copies def_idts[] to idt_table[], which includes many common interrupt handlers.

static const __initconst struct idt_data def_idts[] = {

INTG(X86_TRAP_DE, asm_exc_divide_error),

ISTG(X86_TRAP_NMI, asm_exc_nmi, IST_INDEX_NMI),

INTG(X86_TRAP_BR, asm_exc_bounds),

// [...]

};

void __init idt_setup_traps(void)

{

idt_setup_from_table(idt_table, def_idts, ARRAY_SIZE(def_idts), true);

}

If debugging with pwndbg, you can observe the information of different pages in the CPU Entry Area (CEA) with the command pt -has <address>. Below is an example output:

pwndbg> pt -has 0xfffffe0000000000 # idt_table's mapping

Address : Length Permissions

0xfffffe0000000000 : 0x2000 | W:0 X:0 S:1 UC:0 WB:1

pwndbg> pt -has 0xfffffe0000001000 # cpu_entry_area.gdt

Address : Length Permissions

0xfffffe0000000000 : 0x2000 | W:0 X:0 S:1 UC:0 WB:1

pwndbg> pt -has 0xfffffe0000002000 # cpu_entry_area.entry_stack_storage

Address : Length Permissions

0xfffffe0000002000 : 0x1000 | W:1 X:0 S:1 UC:0 WB:1

Finally, the mapping of cpu_entry_area will be similar to the image below. Note that the relative positions of variables in physical memory may not exactly match the illustration.

2.3 Setup PTE

When PTI is enabled, the initialization function pti_init() sets up the kernel page accessible from user space. This includes the CEA, PERCPU object cpu_tss_rw [1], the kernel entry function __entry_text_start [2], and the exception stack [3].

void __init pti_init(void)

{

// [...]

pti_clone_user_shared(); // [1]

// [...]

pti_clone_entry_text(); // [2]

pti_setup_espfix64(); // [3]

// [...]

}

The PERCPU object cpu_tss_rw, which corresponds to the struct tss_struct struct, is allocated and initialized in cpu_init_exception_handling() [4]. This object appears to be related to exception handling.

void cpu_init_exception_handling(void)

{

struct tss_struct *tss = this_cpu_ptr(&cpu_tss_rw); // [4]

// [...]

tss_setup_ist(tss);

tss_setup_io_bitmap(tss);

// [...]

}

2.4 Mitigation

In older versions, such as Linux 6.1, the struct cpu_entry_area object is mapped at a fixed address (0xfffffe0000001000), providing a known writable memory region that could be exploited for kernel attacks. Additionally, attackers could trigger exceptions to control parts of the exception stack, potentially using it to construct ROP chains. This issue was assigned CVE-2023-0597.

To fix this vulnerability, Linux 6.2 introduced a randomization mechanism for the struct cpu_entry_area. The patch mainly added the function init_cea_offsets() to randomize the PERCPU CEA offset and modified get_cpu_entry_area() to include an offset value before retrieving the CEA address. For more details, refer to the patch commit message.

The init_cea_offsets() function uses get_random_u32_below() to obtain a random value as the offset [1]. It then checks if the previous CEA has a duplicate offset value [2]. Finally, it updates the PERCPU data _cea_offset [3].

static __init void init_cea_offsets(void)

{

unsigned int max_cea;

unsigned int i, j;

// [...]

max_cea = (CPU_ENTRY_AREA_MAP_SIZE - PAGE_SIZE) / CPU_ENTRY_AREA_SIZE;

for_each_possible_cpu(i) {

unsigned int cea;

again:

cea = get_random_u32_below(max_cea); // [1]

for_each_possible_cpu(j) {

if (cea_offset(j) == cea) // [2]

goto again;

if (i == j)

break;

}

per_cpu(_cea_offset, i) = cea; // [3]

}

}

The get_cpu_entry_area() function now adds cea_offset(cpu) before returning the struct cpu_entry_area address, ensuring that the address is not fixed at 0xfffffe0000001000.

noinstr struct cpu_entry_area *get_cpu_entry_area(int cpu)

{

- unsigned long va = CPU_ENTRY_AREA_PER_CPU + cpu * CPU_ENTRY_AREA_SIZE;

+ unsigned long va = CPU_ENTRY_AREA_PER_CPU + cea_offset(cpu) * CPU_ENTRY_AREA_SIZE;

return (struct cpu_entry_area *) va;

}

However, the address 0xfffffe0000000000 is still used by cpu_entry_area (not struct cpu_entry_area) to map the IDT. Since this is just a read-only (RO) page and its contents cannot be controlled, it cannot be exploited for malicious purposes.

3. EntryBleed (CVE-2022-4543)

Even with PTI enabled, user space can still access certain kernel space addresses, which means that kernel addresses can be side-channeled to bypass KASLR. According to “2.2 Setup PTE”, there are mappings in the PTE, such as cpu_tss_rw and __entry_text_start. The former is located in the kernel heap, and the latter is located in the kernel text. If an attacker can manipulate the kernel to access these two addresses, they can use the timing differences in accessing the data cache to determine these addresses. EntryBleed (CVE-2022-4543) demonstrates an exploitation method based on this concept.

he author, Will, uses the prefetchnta and prefetcht2 instructions to fetch data from cache. The prefetchnta instruction fetches data into the nearest cache (usually the L1 cache) without polluting higher-level caches (like L2 or L3). The prefetcht2instruction, on the other hand, fetches data from memory into the L2 cache.

When fetching data, the hardware first checks if the address is cached in the Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB). If the address is present in the TLB, the prefetch instruction is done quickly. If the address is not in the TLB, a full page table walk is required, which takes more time.

By using high-precision timestamp calculations, we can first execute a syscall to cache the kernel virtual address. Then, we can perform a brute-force search across all possible kernel text/heap addresses. When we find a prefetch operation that executes significantly faster than the others, it indicates that the address is already in the cache, revealing the kernel address. Below is the function from the article used for the side-channel attack:

uint64_t sidechannel(uint64_t addr) {

uint64_t a, b, c, d;

asm volatile (".intel_syntax noprefix;"

"mfence;"

"rdtscp;"

"mov %0, rax;"

"mov %1, rdx;"

"xor rax, rax;"

"lfence;"

"prefetchnta qword ptr [%4];"

"prefetcht2 qword ptr [%4];"

"xor rax, rax;"

"lfence;"

"rdtscp;"

"mov %2, rax;"

"mov %3, rdx;"

"mfence;"

".att_syntax;"

: "=r" (a), "=r" (b), "=r" (c), "=r" (d)

: "r" (addr)

: "rax", "rbx", "rcx", "rdx");

a = (b << 32) | a;

c = (d << 32) | c;

return c - a;

}

When a syscall is executed, entry_SYSCALL_64 will be accessed. What about cpu_tss_rw? The CPU register gs_base stores the PERCPU object base address. At the beginning of entry_SYSCALL_64, the user space rsp will be saved to gs:[0x6014] [1], which falls within the same page as cpu_tss_rw (0x6000).

# [...]

<entry_SYSCALL_64+41>: push 0x2b

<entry_SYSCALL_64+43>: push QWORD PTR gs:0x6014 # [1]

# [...]

Furthermore, at the end of the syscall execution, gs:[0x6004] [2] is accessed to restore the RSP, once again accessing cpu_tss.

# [...]

<entry_SYSCALL_64+331> mov rdi, rsp

<entry_SYSCALL_64+334> mov rsp, qword ptr gs:[0x6004] # [2]

<entry_SYSCALL_64+343> push qword ptr [rdi + 0x28]

# [...]

In other words, even with PTI enabled, it is still possible to leak kernel text and heap addresses through side-channel methods, thereby bypassing KASLR.

4. Real World Case

The kernelCTF has CONFIG_PAGE_TABLE_ISOLATION=y enabled, meaning the PTI alternative code is compiled into the kernel. However, by examining the output of cat /proc/cpuinfo, we can see that the CPU “Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU @ 2.80GHz” is not affected by Meltdown, so PTI would not be enabled. If it were affected, the bugs section would include "cpu_meltdown".

# [...]

bugs : spectre_v1 spectre_v2 spec_store_bypass mds swapgs taa mmio_stale_data retbleed eibrs_pbrsb gds bhi

# [...]

So currently, most kernelCTF players are using EntryBleed to bypass KASLR.

5. PCID

Process Context Identifiers (PCID) is a mechanism designed to reduce the overhead caused by flushing the TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) during context switches. Each process has a unique virtual memory mapping, requiring the flushing of non-global TLB entries with every context switch. Ideally, PCID assigns a distinct ID to each process and sets this ID in the TLB entry. During TLB access, only entries with a matching PCID to the current process are checked, ensuring that TLB entries are not shared between different processes. Consequently, this eliminates the need to flush all TLB entries.

PCID is supported only on the x64 and is disabled by default. Enabling it requires setting bit-17 (PCIDE) of the CR4 register. Once enabled, the PCID is stored in the lower 12 bits of the CR3 register. Because of only 12 bits being available, it doesn’t practically assign a unique PCID to every process, and even if unique IDs could be assigned, the entries filled with different processes could slow down TLB access. Therefore, it needs a lot of optimizations when applying PCID to the OS.

Typically, TLB flushes occur when updating the page table, specifically when writing to the CR3 register. The PTI mechanism necessitates frequent switches between user space and kernel page tables, leading to constant TLB flushes and significantly reducing performance. However, with PCID enabled, switching page tables no longer requires flushing the entire TLB, thereby greatly decreasing the performance impact. Let’s see how the Linux kernel enables PCID!

The init function get_cpu_cap(), called by setup_arch(), runs the cpuid instruction to obtain the current CPU’s supported capabilities. If bit-17 (0x20000) of the returned ecx [3] is set, it indicates that the CPU supports PCID.

void get_cpu_cap(struct cpuinfo_x86 *c)

{

u32 eax, ebx, ecx, edx;

// [...]

if (c->cpuid_level >= 0x00000001) {

cpuid(0x00000001, &eax, &ebx, &ecx, &edx);

c->x86_capability[CPUID_1_ECX] = ecx; // [1]

}

// [...]

}

After that, the setup_pcid() function is called to initialize PCID. This function checks whether the architecture is x64 [2] and whether the CPU supports PCID [3]. If both conditions are met, it sets the PCIDE bit in CR4 to enable PCID [4]. (some details are omitted)

static void setup_pcid(void)

{

if (!IS_ENABLED(CONFIG_X86_64)) // [2]

return;

if (!boot_cpu_has(X86_FEATURE_PCID)) // [3]

return;

// [...]

cr4_set_bits(X86_CR4_PCIDE); // [4]

// [...]

}

You can still check if the CPU supports PCID after booting by looking at /proc/cpuinfo.

cat /proc/cpuinfo | grep -i pcid